Describing Ott in just a few words is quite a challenge. He is a UK-based musician, producer, and sound engineer who has been delivering exceptional albums for over two decades.

His work features psychedelic bass, ethereal melodies, and inspiring soundscapes, all crafted with remarkable quality. He has collaborated with artists such as Brian Eno, Simon Posford, The Orb, and Sinéad O’Connor.

Following an interview in 2020, it’s a pleasure to continue our conversation with him.

Interview by psybient.org team on 24/01/25.

Hi Ott, how are you? Thank you so much for taking the time to chat with us.

I’m well, thank you. It’s a pleasure.

Are you currently in Exeter? What’s the winter season like there?

I’m about 10 miles south of Exeter and it is cold, grey and raining.

Let’s kick things off with a brief question: who is Ott as an artist?

Inseparable from the Ott who takes a bath or walks the dog. Just a random collection of signals imprinted on a nervous system.

Your new album, Hiraeth, is a journey. What concepts and vision inspired it?

Everything I’ve ever seen, heard, felt or done, same as all the others. Making music is a constant process which probably looks like a series of separate albums from the outside but which feels seamless and never-ending from my side.

How has your approach to music-making changed in recent years? Are there any new techniques or ideas you’re exploring right now?

Yes, I’m trying harder than ever to shut my conscious rational mind out of the process and let my subconscious do it all.

Reflecting on your career, could you share a bit about your musical journey?

In 1982 aged 14 I desperately wanted to be in Depeche Mode but they weren’t hiring so I decided to go it alone. By 16 I had a Roland SH101 synthesiser and a tape recorder but no songs. I made hundreds, thousands of strange cassette recordings of me trying to figure out how sound works and by 18 I was playing synths in a band. A terrible band. My terrible band made some terrible demo recordings but while in the studio I fell in love with the process of layering sounds on top of each other and decided I wanted to be a studio engineer.

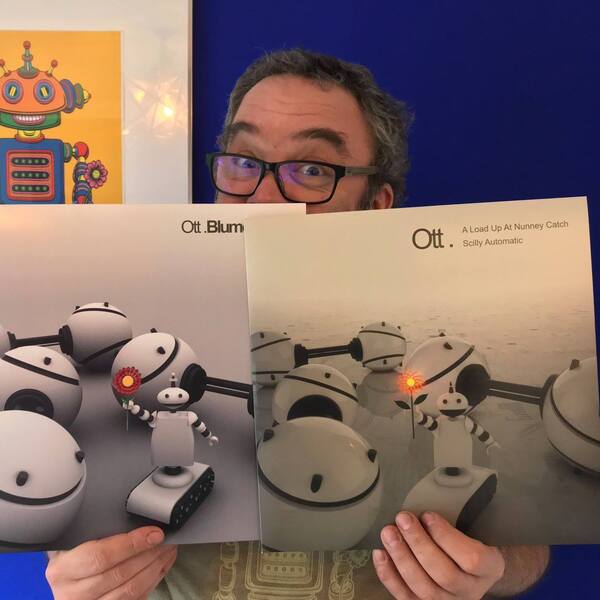

It took me two years to lie my way into that job [I told the studio manager I had five years experience when I’d only been inside a recording studio twice in my whole life] and I was a freelance studio engineer all through the 1990s. At the end of the ‘90s I decided I’d had enough of recording other people’s music and started writing some of my own and those early experiments became Blumenkraft. In 2002 I made an album called Hallucinogen In Dub for Twisted Records and since then I have released a total of seven albums with another on the way.

Can you describe a typical day in your studio and how you organize your creative time?

I usually go to bed late, sleep for eight hours, get up, make a cup of tea and carry on where I left off. I tend to put in 18-hours days but a lot of that time is spent staring out of the window feeling envious about Vince Clarke’s RSF PolyKobol or Richard James’ Korg PS3300.

Also, could you give an example of a recent piece of equipment or software that has notably impacted your creative process?

There is a company in Amsterdam called This is Not Rocket Science who make the most exquisite synthesisers and what they do has fundamentally changed what I do. They design and build these super-precise, super-sloppy, random, predictable machines and they send me prototypes to play with. A couple of years ago, in partnership with the original designers they released an updated version of the super-rare, highly-coveted Dutch synth the Synton Fenix and this, along with a couple of racks of their Eurorack modules, has become my main instrument. They also contribute synth parts and vocals to my songs. I am fortunate to know such people.

What specific environments or settings do you find most inspiring for creating music?

A windowless, airless room with an uncomfortable chair and too long between toilet breaks.

Are there any upcoming projects you would like to share with us?

It’s just me, doing this, forever. Actually, Chris has his work-life balance a bit better now so there is the remote chance of an Umberloid album happening but I’ve been saying that for 20 years so just ignore me.

Do any non-musical art forms, such as painting or film, influence your work?

Yes, hugely. In my studio I have an iPad playing randomly from a collection of post-war ephemeral film, industrial film, documentaries, public information films, etc. My main interests are UK town planning and transport infrastructure from 1948 – 1984 and I have eleven days of films to randomly choose from.

I’m interested in the subject matter but I’m more interested in the production techniques, editing styles, audio recordings, use of colour and angles and how they worked with such primitive equipment to produce such visually pleasing results. 16mm film is like a

massage for the eyes.

How do you see the future of psychedelic electronic music evolving in the coming years?

Impossible to predict. Technology and culture are ever-evolving and the pace is quickening. I can do things with sound today that I wouldn’t have imagined possible even ten years ago. Evolution is inevitable. Unless it’s psytrance. In psytrance it’ll be 1998 forever.

Outside of music, what hobbies or activities do you enjoy to relax and replenish your creative energy?

I like to ride my motorcycle, sit on a clifftop making breakfast in one pan, throw sticks into the sea for the dogs, walk in the woods, stare out of the window at the birds.

And before we wrap up, would you like to share a message with the readers, listeners, and supporters of psybient.org?

“We are seeing here, the fundamental principles of drama.”

Thank you so much for your sounding words. We’ll keep riding the waves, swimming, and diving deep into the Ott sonic oceans. Sending hugs!

Thank you for listening. Makes it all worth it. :0]

![[interview] with Easily Embarrassed (by Mønsterhed)](https://www.psybient.org/love/wp-content/uploads/Easily-Embarrassed-2.jpg)

![[interview] 5 questions with Gabriel Le Mar (Saafi Brothers)](https://www.psybient.org/love/wp-content/uploads/Gabriel-Le-Mar-Saafi-Brothers.jpg)